Contents

All over airplanes, the words “emergency use only” label life vest compartments and door levers, but there’s no such warning for the button above each passenger that’s identified only by the outline of a person.

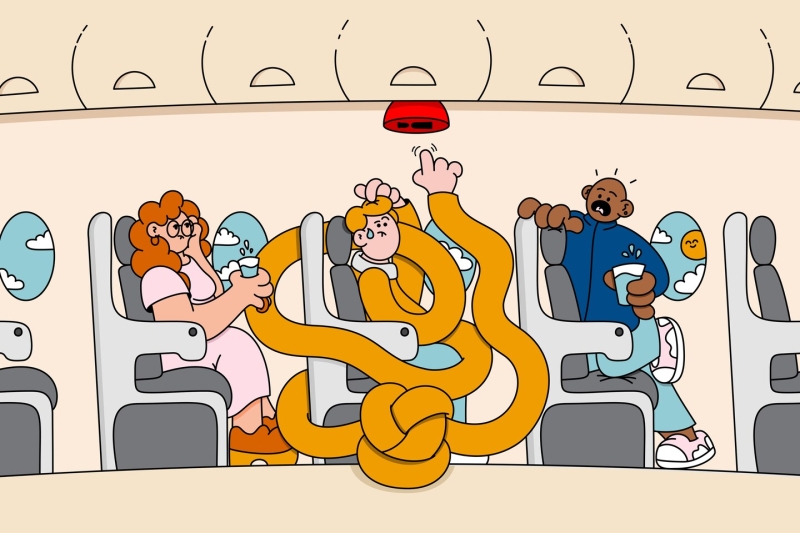

If we press it, a flight attendant will appear. Before takeoff, they’ll tell us about seat belts and inflatable escape routes, but you could fly a lifetime and never hear a peep about the proper use of the call button. I began to wonder about this after the last time I hit it, when a flight attendant arrived and asked, “What’s your emergency?” My emergency? I hadn’t realized the button was the 911 of the sky.

Most of us have probably hit this button at least once, for a drink if it seems as if there’s no more service or a blanket if it feels like ice crystals have formed on our kneecaps. But some people say they’d have to be inches from death to use the call button. Does that make the rest of us oblivious?

A rise in unruly passengers shows us flight etiquette is out of control. Those of us who want to be polite travelers (but also might need a water) would love to know when exactly it’s appropriate to make the little ding, so I asked those for whom the ding chimes.

Have a little patience

Travelers aren’t the only ones with mixed feelings about the call button.

“It’s our frenemy,” said a flight attendant who has been working with American Airlines for six years and who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect his job status. “We love it and we hate it at the same time.”

He likes that it’s there in case of emergencies. He can hit one above a seat from up front to let a colleague in the back know he needs something, then perhaps mime a glass for them to bring up a soda. He also said it’s preferable to people poking him or tapping him on what, with his 6-2 frame, tends to be his butt.

So they love the button for communication. And why do they hate it?

“Oh boy,” he said. “Just because, you know, they’ll ring that call light for days. And I’m like, ‘I already got it. I see you, like, I’ve made eye contact with you. I told you: Give me one moment if I’m busy.’ And they’ll keep ringing it.”

In short: Don’t be that person. He said a better way is to catch a flight attendant’s attention as they’re walking and raise your finger.

Bad passengers and $37K a year: Who wants to be a flight attendant now?

Flight attendants’ No. 1 job is safety

What flight attendants can agree on, but the general public misses, is that they are fundamentally concerned with safety, not Biscoff cookies. We see flight attendants give out food, serve drinks and take our trash, which makes their job appear to be like something akin to hospitality.

What we may not notice is them ensuring we’re wearing our seat belts, seeking out anything that could be a weapon, listening for anyone becoming belligerent, skirting any statements that could get them sued, preventing a scene that could get them shamed on social media and communicating with each other about anyone who could attack, while also checking to make sure the engine isn’t billowing smoke.

“A lot of people don’t see that, which — I get it,” he said. “Before I became a flight attendant, I didn’t see that. I just thought, ‘Girl, you better give me my soda.’”

Out of 6½ weeks of training, he said only one day covered the soda side of their work. The rest focused on keeping travelers alive.

If you are in danger or having an emergency, please do ring the call button twice, according to our source.

“Flight Attendants are generally trained to treat the call button as [a] potential emergency and will respond accordingly,” Taylor Garland, communications director of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, said in an email. “It’s not a vodka tonic button.”

FAA will require more rest time for flight attendants

Check the phase of the flight

Veda Shook, who works for Alaska Airlines, has been a flight attendant for more than 30 years. She has gotten clicks and snaps to get her attention, and she’s responded to call-button dings for drinks, trash and spills.

“It could be they’re in distress or somebody else is in distress. I mean, that does happen,” she said. “That is why [the buttons] have to be there.”

She’s also had someone hit the call button because a baby was crying near the passenger and she “needed” to move. “And if you send your children on their own, you know, sometimes kids really like that button,” she said.

Shook sympathizes with today’s passengers. Over her career, she’s seen “less staffing and bigger planes.” She cringes at the TSA lines bursting at the rope dividers and the security agents barking at the people about to board.

If you’re considering pushing that button, Shook said, start with understanding which phase of the flight you’re in.

If the plane is on the ground and the flight attendants are in their jump seats, “I am going to assume that’s an emergency, up through at least 10,000 feet of altitude,” Shook said. “Up to cruising altitude, don’t ring it unless you need to ring it, honestly.”

Each trip is different, depending on the airline, duration and time of day, but you’re most likely to have at least one round of food, then drinks, then trash pickup. A service for water refills might come later. On longer flights, a repeat.

Don’t expect a smile if you called a flight attendant after they were just out in the aisle, or if they’re in the back preparing a cart. Shook said that if she’s going through and picking up trash, and three people ask her for water, she might remind them that she’ll be coming right out with water for everyone soon.

Shook said flight attendants will usually be visible about four times an hour, so if you need something, chances are you’ll see someone within 15 minutes.

So when is it appropriate to summon a flight attendant to your seat, if ever?

“When the seat belt sign is off, and the plane is at altitude, and you haven’t seen the flight attendant in at least 15 minutes,” Shook said.

Paulette Perhach is a Florida-based writer. You can follow her on Twitter: @pauletteperhach.